Members of What, How & for Whom/WHW

From the January 2019 edition of Grantee Voices

Members of What, How & for Whom/WHW

From the January 2019 edition of Grantee VoicesEriola Pira: We’re sitting here outside Galeria Nova in Zagreb, which What, How & For Whom has been running for some 15 years, and I wanted to start our conversation this afternoon, Ivet, with the history of WHW: how you, Ana Dević, Nataša Ilić, Sabina Sabolović, and designer and publicist Dejan Kršić came to work together as a curatorial collective. What was the impetus behind your practice, and how have you maintained the relationship through the many years of working together?

Ivet Ćurlin: The first exhibition organized by the collective happened in 2000. It was called What, How & for Whom, dedicated to the 152nd anniversary of the Communist Manifesto, and it took place in the main building of the Association of Croatian Artists here in Zagreb. It was an exhibition triggered by the fact that the republishing of the 150-anniversary edition of the Communist Manifesto, with a preface by Slavoj Žižek, by the publishing house Arkzin, had gone by completely unnoticed in Croatia. The exhibition was curated by Ana Dević, Nataša Ilić, and Sabina Sabolović in collaboration with Arkzin Magazine. Dejan Kršić, who was the designer and editor of Arkzin at the time, is the WHW designer and a collaborator to this day. The exhibition looked into issues around the economy and the transition from the socialist to the capitalist system. What brought it about? What were the things that happened in this process but were not discussed in public discourse? These questions, and the idea of establishing links with the past—challenging the notion that nothing that happened before 1991, when Croatia gained independence, was of any value or consequence—as well as the importance of establishing links with the former Yugoslav republics became immediately clear. These two directions remain constant for the collective.

I joined the team after I returned from my studies in the US, maybe two weeks after this first exhibition opened. We discussed how to continue working together; in 2001, we formed an association. Soon afterwards, we worked on our second exhibition, Broadcasting Project, dedicated to Nikola Tesla, at the Technical Museum. Similar to the Manifesto exhibition, which was not about the manifesto but about the economy and questions of this post-transitional - or, at the time, transitional - society, the broadcasting exhibition was not about Nikola Tesla. It was an exhibition about freedom of information, copy laws, about what an invention means—what is the relationship between the flow of information in contemporary art and in the contemporary world? But, of course, at the time, the dedication to Nikola Tesla was also a rather direct political statement. Nikola Tesla was a Serb from Croatia who, when we were growing up, was a local hero; then suddenly in the 90s, he was persona non grata. His monument in Gospić, a town near his place of birth, was blown up in 1992. On the other hand, it was also the early 2000s, and a space of possibility was opening; you could say things in public you couldn’t have only a few years before. In fact, our next project was called Normalization, and we acknowledged that we talked about certain things at a time when the space for talking about them was being opened. In 1995, one wouldn’t be able to say these things in a public space or not as easily, at least. So, in a way, the members of WHW, from the very beginning, were connected by a political as well as an aesthetic affiliation. We had the same notions and beliefs about what art can and should do—the ability of art to challenge the traumatic issues in society, to open them up. And to be a kind of questioning ground, to expose the neurotic points rather than represent national identity.

EP: Looking back at the collective’s exhibition history, it becomes clear that history, be it through the Communist Manifesto or Nikola Tesla, is active and present in contemporary life. In much the same way, your curatorial practice has been distinguished by working with and encouraging an intergenerational conversation between artists of the 70s and a younger generation of artists working today.

IC: It is work that we grew up with and learned from—the artists of the new artistic practice of the 1970s, such as Mladen Stilinović, Sanja Iveković, Vlado Martek. When we were at university, these artists were known, of course, but also not established that much institutionally, especially in the 1990s when there was a collapse of institutions. They never taught at any of the art schools, there was not that much published about their work, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, which was a very important and strong institution throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s in terms of production of content, had pretty much collapsed in the 1990s. Their new building was not built yet, so the collection was in storage, and if you wanted to know something about the art of the 1960s and 1970s, you had to contact the artists directly. In a small place like Zagreb, you can do that, and they are very open and friendly; it’s easy to approach people.

EP: But you also took care to contextualize and connect their work internationally, not just locally—treating them as local heroes.

IC: Yes, maybe because of this really strong reflex against nationalism and the question of national representation and what does it mean to be a Croatian artist, Serbian artist, whatever. We never did a Croatian show. No, in fact, we did once. It was the pavilion of Croatia at the Venice Biennale in 2011 with Tomislav Gotovac and the BADco, which is a performance collective. But even then we tried to move away from the standard representation of “the national artist." Whenever we were invited to do exhibitions that would be nationally or geographically representational, an exhibition of Croatian, or Balkan, or Eastern European artists, we would just do something else. We would do an international exhibition with a topic pertinent to that particular location and context where the exhibition was taking place, and then try to contextualize artists from Croatia and from the region.

One Needs to Live Self-Confidently...Watching, an exhibition of the work of Tomislav Gotovac and BADco, curated by WHW, at the Venice Biennale in 2011.

Photo: Ivan Kuharić

One Needs to Live Self-Confidently...Watching, an exhibition of the work of Tomislav Gotovac and BADco, curated by WHW, at the Venice Biennale in 2011.

Photo: Ivan KuharićEP: I’d like to go back to the question of being a collective: of being more than just a group of people who have an affinity for the same artists or are reading the same magazines. Starting with Marx, as you did, already said something, but in what way has working collectively also been a political statement for you?

IC: Working collectively allows us to do things that we wouldn’t be able to do on our own. In terms of efficiency but also programmatically. You are right, when you say to somebody that we are working together for 19 years now, people usually get confused and don’t understand how it's possible. We aren't trying to gloss it over and say this is easy and without conflict, but it does enable us to create a platform to work on a program. That is also a political statement. Having been around long enough, we’ve continuously worked on overcoming our differences and continuing together: creating a platform, a new model of a semi-institution, or maybe a new model of a hybrid institution. But there are also downfalls with that as well! Because you also self-exploit and self-instrumentalize in many different ways. And there is always a certain dialectic in this tension between trying to develop a political program and trying to develop an efficient institution, trying to develop an activity that is enjoyable to you and also struggling to continue working even when what you do at the moment is demanded by institutional logic, not by individual enjoyment. When you work on a certain project for 20 years, different aspects of it open up through different projects. What is also nice is the balance we have in our work between our international and local presence and work at Gallery Nova, a space that we have been running for 15 years now, where we have a platform to do things on a regular basis: to engage with the local audience, to do projects that are fairly low-key and grounded in our struggles on a local level. And then there are the invitations we get from abroad that come from institutions of various sizes and profile. These challenge us. Every time you enter into a collaboration with a certain museum, festival, or program you need to learn how to work with them; you have to build knowledge around the context for which you are creating the exhibition.

EP: Since you brought it up, let’s talk about both the challenges and the benefits of working internationally and what that has meant to you but also more broadly: what do you value about working internationally or even regionally as you hinted at earlier?

IC: What is happening here in Croatia is just a tiny part of what is happening everywhere. By working internationally, you’re ultimately trying to figure out your own place in terms of what is happening here in Croatia economically, politically, in relationship to what is happening in the Middle East, in relationship to what is happening in the West. Working internationally helps you to learn, to grow, to do research, to learn about artists and their practices, to promote and contextualize artists from here, to build lasting international networks. Also, for us in the precarious and very strange local situation, working internationally brings a certain kind of recognition here. We wouldn’t necessarily have had that if we weren’t internationally successful. Whatever we do internationally helps us work here, and we consciously connect it with what we do here, both in terms of content and pragmatically. When we do a long-run international program—as we did for the Istanbul Biennial—things that we did around Istanbul were also coming back to the gallery. Aware that many people from Zagreb would not see the biennial, we did a program, Istanbul in Zagreb, based on the research we were conducting. During the two-year long process before the biennial, while we were developing projects with artists, working here in Zagreb was also a certain testing ground. Or differently, after the biennial, we continued to work with artists in Zagreb. For several years, programs resulted from the research and collaborations developed through the Istanbul exhibition.

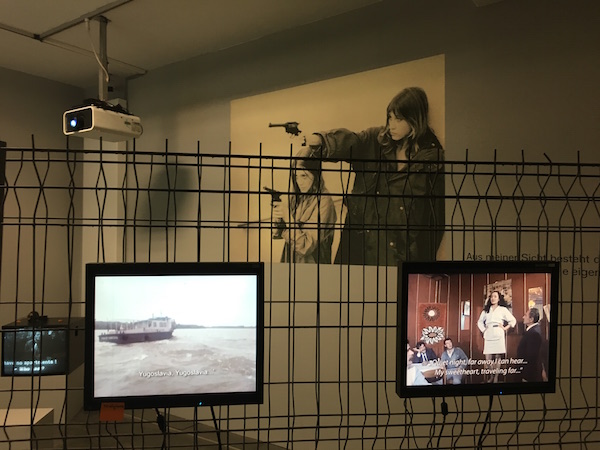

Similarly, the research and knowledge we gained when curating an exhibition at the Reina Sofia in 2014 also resulted in an exhibition that happened later in Zagreb. Now when we did Shadow Citizens, the retrospective of Želimir Žilnik, at The Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg, Germany, of course, we will do the exhibitions of Želimir Žilnik in Gallery Nova later this year as well. We developed this methodology of long-term projects and activities evolving from each other and building upon each other to allow ourselves more space for research and thinking, and to counter, at least a bit, the neoliberal demand for ceaseless production of new activities, for delivering new things all the time. In this way, we try to do things strategically, to develop activities around the lines of inquiry that really interest us. We feel less like we are running all the time—and that we are learning while doing things, researching certain subjects in depth. This is why if you look at our projects, very rarely is there an exhibition that's only just one thing; there will always be a series and a continuation. As an art critic once wrote about our work: “They are doing all the time one exhibition, anyway.” One exhibition extended over time.

Shadow Citizens at The Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg, Germany.

Photo: Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art

Shadow Citizens at The Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg, Germany.

Photo: Edith-Russ-Haus for Media ArtEP: It is a nice way of putting it, actually. There is a value to sticking with the same subject matter, conversation, or commitment to a few artists over time. Going back to this neoliberal drive to do multiple projects with as many people and in as many different places, it doesn’t always allow for in-depth research, collaboration, or engagement with different kinds of artists, communities, and the public. Which brings me to your residency and collaboration with Clockshop, which was funded by the Trust for Mutual Understanding. How did that come about? I’m curious about this “rethinking the local” you were working on there.

IC: Well, it came about as a result of these long-term conversations and collaborations we’re talking about. We met Julia Meltzer and David Thorne, who were at the time working as Speculative Archive, during our research visit to Los Angeles in 2007. They did the film We will live to see these things, or, five pictures of what may come to pass in Syria, which was shown at the Sharjah Biennial in 2011, where we saw and loved it. We invited Rasha Salti, one of the curators of that edition of Sharjah, and Julia and David to the Sweet Sixties seminar in Zagreb at the end of that year. Incidentally, their visit to Zagreb was also funded by the Trust for Mutual Understanding. We’ve since stayed in contact, and we showed this film on several occasions in screening programs and teaching sessions. When I was at Engage More Now! Symposium at Hammer Museum in 2015, Julia and I met and planned WHW’s residency in Los Angeles. So, our visit was the result of a collaboration that has been going on for several years, and it was a really nice residency. We also invited artist Vlatka Horvat to join us, and she did a performance as a part of Clockshop Bowtie project. We had a public talk with Made in L.A. curators Erin Christovale and Anne Ellegood, which went really well, and we also met quite a few people with whom we’ve collaborated since, such as curator Sohrab Mohebbi or artist Miljohn Ruperto, both of whom later came to Zagreb and were part of Gallery Nova program, again, with TMU support. Miljohn Ruperto will be taking part in On the Shoulders of Fallen Giants, 2nd Industrial Art Biennial, an exhibition we are curating in Labin, Pula, Raša, Rijeka, and Vodnjan.

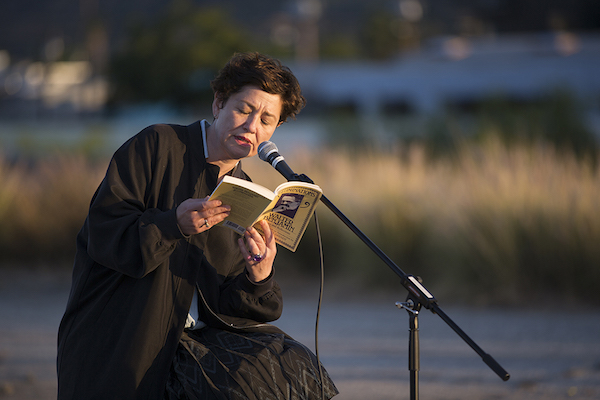

Beginnings Marathon by Vlatka Horvat at Clockshop in Los Angeles, CA in May 2017.

Photo: Sara Pooley

Beginnings Marathon by Vlatka Horvat at Clockshop in Los Angeles, CA in May 2017.

Photo: Sara PooleyEP: I’m interested in this idea of working locally but also sustaining international collaborations—how you described working internationally as a way of learning and of putting things in perspective. And I’m wondering what those two weeks in LA after the 2016 election were like for you? What, if anything, did you learn from being in the US during that time?

IC: Actually the talk, Curating Within a Heightened Political Moment, that we had with Anne and Erin was part of a series of talks that Clockshop held after the election called Counter-Inaugural. It was a discussion on how does art position itself in politically difficult times, how Anne and Erin will try to structure Made in LA in light of the political changes in the US, and how do we engage with the rise of right-wing ideology in Europe. In terms of experiencing the US in the aftermath of the election, it was a rather short visit so, for me, experiencing the US in the aftermath of the housing crisis was much stronger. The last time I was in Los Angeles for a bit longer time was in 2007. During the 2017 visit, I was shocked by the increase in the number of homeless people. This was something we talked a lot about with LA residents. One of the nicest studio visits we had was with LAPD (Los Angeles Poverty Department). It’s a 20-year-old theater group and an art project that is developed by the homeless, or formerly homeless people, on LA’s Skid Row. It was interesting how no one mentioned them during our previous visits, but during this residency, several people suggested we meet LAPD. And then we came to LA and realized after one drive around the city why this is the most important topic. Homelessness and issues around basic living. Every underpass in the city has people living there. It was very shocking, something I don’t remember from ten years ago. There are tents in the parks. This provided some context about how society as we know it has been radically challenged.

EP: Do you see cultural institutions responding to the current political moment, which, as you say, is a symptom of the global financial crisis? In the US, we saw institutions take immediate steps to position themselves in the aftermath of the recent US election, but those same institutions were also the ones whose structure may not have been ready to take on such leading roles. I think we’ve seen individuals or, at best, departments at various cultural institutions take positions that may have put them at odds with board members, funders, and segments of the public that would like to go on believing art institutions are neutral to begin with.

IC: I’m not sure. Some are responding, some are not. I think it has been erratic. Most responses are coming from the smaller institutions rather than the bigger ones. For bigger institutions, it’s business as usual: quite representational exhibitions that are beautiful and interesting but are, in most cases, non-problematizing. There are very few institutions, especially in the West, like Reina Sofia in Madrid or Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, who have been leading the way.

EP: Let’s return to Croatia where you’ve recently launched and are running WHW Akademija, a new international art study program. What led to this next chapter in WHW’s curatorial practice? What was the impetus for creating an educational program? What do you hope to provide to participating artists in this particular moment?

IC: It’s about building in-depth, long-term relationships with a younger generation of artists, not necessarily just by coming in and doing a studio visit. We feel there have been several factors that were quite unfavorable for developing art scenes in Croatia and in the wider region: many donors pulled out of Eastern Europe, the institutions are still not doing their work on building critical discourse and contextualization, this area of the Balkans was really hit hard by the economic crisis, and, at the same time, it also became a bit out of fashion in international art world circles. As a result, new networks among artists from different countries are not developing; there is again a sense of isolation in their own little countries and situations. This has created a feeling of being lost and left out among many artists of the young generation. We have been talking about starting a study program that would try to counter this for quite awhile. How to do it, and what would the model be? We are very much inspired by what Ashkal Alwan did. We thought a study program could be developed here in Zagreb; it would be a space to work on strengthening the link between practice and discourse. Also, the goal is to strengthen regional networks and bring more people to Zagreb to create new dialogues and connections among artistic disciplines, which, here, are often sharply divided into “traditional” and “contemporary” in an uncritical and unproductive way.

EP: So it will be an international program with an international student body as well as faculty and guests?

IC: Yes, the program will be international. We would like to focus on the region, but we’re not excluding people from anywhere. The open call for WHW Akademija is going on now; we’re very excited to see where we get applications from and what they will be like, which will, in a way, very much determine the program. We know for sure who the resident professors for the next year will be: Ben Cain, Tina Gverović, and Sanja Iveković. Also, we know who the guest professors, for lack of a better term, will be: Pierre Bal-Blanc, Rajkamal Kahlon, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, and Adam Szymczyk; two curators and two artists who will spend two weeks each with the students. We will also have a number of people coming for shorter periods of time, let’s say 3-4 days, to hold closed seminars for the students and public events and lectures for the general public. There will also be a joint studio working space for the students.

EP: Aside from you giving us a peek into some projects that are in the pipeline, what exhibitions are you working on?

IC: The exhibition on which we worked intensively during this year was 2nd Industrial Biennial: On the Shoulders of Fallen Giants, organized by a non-profit organization, Labin Art Express, in the Istrian peninsula of Croatia. Labin was one of the biggest, strongest mining towns in the former Yugoslavia. The whole mining area was heavily developed by the Italian Fascist government. Later, it fueled the socialist economy in Yugoslavia, and the coal mines closed fairly late, the last parts only in 1998. The biennial was created four years ago with the intention of revitalizing the spaces of the former mines in and around the city of Labin. This edition took place in five locations: Labin, Pula, Rijeka, Raša, and Vodnjan, from July to October. It examined Istria as a region that was actually always on the border of empires and has changed hands many times; but throughout the war-torn 1990s, it was the most tolerant region of Croatia. It is also a place that has a certain mystique, sometimes it is a bit mystified as an exotic and magical place. Through a number of new art productions, the exhibition attempted to explore different strands of this story about the locality in Istria based on this notion of the fallen giant, the discarded but now also resurrected historical knowledge. The other thing that we are working on is a publication on Želimir Žilnik that we are preparing as a continuation of the retrospective we did in May in the Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst in Oldenburg. That will open in Gallery Nova in November. We will actually be preparing two new publications in 2019. One is the book on Žilnik, the other is a reader that will be a conclusion to the project My sweet little lamb (Everything we see could also be otherwise) in which we collaborated with the Kontact Art Collection from Vienna—it unfolded in six episodes in Zagreb, with an epilogue in London last September. Aside from this, all of our efforts are focused on the Akademija, which will take place from October 2018 to June 2019.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––What, How & for Whom/WHW is a curatorial collective formed in 1999, based in Zagreb and Berlin. Its members are curators Ivet Ćurlin, Ana Dević, Nataša Ilić and Sabina Sabolović as well as designer and publicist Dejan Kršić. WHW organizes a range of productions, exhibitions, and publishing projects and directs Gallery Nova in Zagreb. WHW has been intensively developing models based on collective way of working, collaboration between partners of different backgrounds, and involvement with local advocacy platforms. What, how and for whom, the three basic questions of every economic organization, concern the planning, concept, and realization of exhibitions as well as the production and distribution of artworks and the artist's position in the labor market. These questions formed the title of WHW's first project, What, How & for Whom, dedicated to the 152nd anniversary of the Communist Manifesto, in 2000 in Zagreb and became the motto of WHW's work as well as the title of the collective.

Eriola Pira is a New York-based art curator and writer. Most recently, she served as the director of programs at Art in General and was previously the program director and curator at NARS Foundation. For close to nine years, she directed the Young Visual Artists Awards, an international artist exchange and New York residency program in partnership with 11 art organizations in Eastern Europe. She has curated exhibitions, produced public programming, lectured across Europe and the US, and worked with such institutions as: The Studio Museum in Harlem, Independent Curators International, Exit Art, NURTUREart, BRIC, International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP), and Residency Unlimited. As an editor and writer, her work has appeared in Guernica Magazine, Bomb Magazine, Huffington Post, and Kosovo 2.0.