András Török: I am sitting in the brand new Glassyard Gallery in Budapest with Barnabás Bencsik, who is the curator and co-owner of the gallery, launched at the end of September 2017. Barnabás, you are a well-known curator—you have had a long career. I’m interested in the international aspects of your career. Actually, have there been aspects other than international ones?

Glassyard Gallery

Glassyard GalleryBarnabás Benscik: (laughs) I suppose the international dimension does not exist without the local, being rooted in the local scene. So, my international career is about representing Hungarian arts in the global scene.

AT: Can you summarize the three most important phases of your career? Let’s begin with when we first met. At that time, you were part of the Studio of Young Artists Association.

BB: Yes, I ran the Association’s Studio Gallery from 1990 until 1999. This was the period when the younger generation of artists realized that there is a completely different world around the contemporary art scene than what was known to them before. During the Socialist times, Hungary was pretty much isolated from the art world—especially from the contemporary art world. In my position of being responsible for the Studio Gallery program, it felt somehow compulsory to try and set up a network with the international scene: to provide artists with an opportunity to look around outside of Hungary’s borders, to introduce them abroad, and to help them create their own personal networks. So, we initiated exchange projects. We had specific programs with Pro Helvetia in Switzerland and the British Council in London, and we had a collaboration with the Dutch scene during the ’90s. These initiatives were quite enthusiastically supported by foreign organizations. Pro Helvetia had a three-year program that supported Central and Eastern European countries. We applied with a specific program to develop connections and a network between the Swiss and the Hungarian art scenes with different projects like exhibition exchange, institutional collaborations, residency programs, and so on. This was the most effective way to introduce the younger generation to the international scene. The same idea was realized with the British Council project, which also ran for three years. With this project, we had an opportunity to design something that would run for a longer period, so we made it a structured program that supported research trips to London not only for artists but also curators and art critics. London was one of the most exciting cities in the ’90s. It was the time when the Young British Artists (YBAs) were just starting to get international recognition. This is the YBA, the Damien Hirst generation. We also initiated a very special type of exchange—a program between artists where they swapped apartments. They would spend—as I remember—one or two months in the other artist’s social ambience. It was, of course, shocking for the Hungarian artists, and it was also really exciting for British artists, like Tacita Dean or Bridget Smith, visiting Budapest.

AT: How was it exciting for the British artists?

BB: Their experiences were quite surprising for me. For example, the London-based artists in Budapest were amazed by how easy it was to get to nature. If you are living in the city, it’s really easy to get to the forest. In London, it seems impossible. There were a few local artists who had apartments on the Buda side of the Danube, and the guests were just amazed that with a ten-minute walk, they were in the nature, in the Buda forest.

AT: What happened when this initial interest in the ’90s for Central and Eastern Europe passed? In the early 2000s, nobody was interested in Central Europe anymore.

BB: Hungary entered the EU in 2004, and everybody thought, “From now on, the country will operate in a normal way.” But this actually wasn’t true at all. (laughs)

AT: Where did you work at that time?

Trafó House of Contemporary Arts

Trafó House of Contemporary ArtsBB: I worked for two years at Trafó; I ran the gallery there. It was a different type of challenge. Trafó was an ICA type of contemporary arts center with dance, theatre, music, and visual arts. In the dance and music fields, Trafó was completely on the international standard. It was part of international networks involving similar types of institutions from the US, UK, Canada, and Holland. Trafó was a constant collaborator in international projects, but the visual arts programming was not on the same level. It was a challenge for me to try to push it up to that position. Because it was a brand-new institution, personal credibility was really important. The Trafó gallery needed to join certain networks and make connections and credits—make a name for itself. It was a challenge to position Trafó as an exhibition venue. I suppose my tenure there was successful in the sense that my successors continued in this direction. Right now, Trafó is the most international contemporary art exhibition venue in Budapest, which is really important for the local scene.

AT: Then you had a relatively short adventure with a new, privately owned institution.

BB: Yes, that was in the beginning of 2000. It was called MEO. It was a really ambitious initiative.

AT: We loved it.

BB: It was established by two businessmen: one from the commercial gallery world, who focused on early modernism and contemporary art, and his friend who was deeply involved in the privatization process in the ’90s.

AT: An “affluent guy.”

BB: (laughs) Yes, so to say. He was involved in the leather industry; he bought a former leather factory in Újpest, which is a Northern district, an industrial district of Pest. Following his gallerist friend’s inspiration, instead of starting industrial production there, he turned it into a cultural hub. This was the first example in the Central European region of turning a former industrial building into an exhibition space - as initiated by a private person. Actually, it was quite successful in the sense that it was a very well-designed exhibition space. The total space occupied more than 2400 square meters, which is competing with the Künsthalle. It became the number one venue for contemporary art. I was invited to run the program there, and I immediately realized that the only way to fulfill expectations was to gain international recognition. So, we made some really successful exhibitions of the work of international artists. For example, Andres Serrano had a huge show there. It was a massive success among the Budapest audience. But after one year, we fell into the trap of every private institution. If an institution is private, there has to be a personal motivation behind it. If that personal motivation changes, the original idea becomes completely distorted. After a year, I had to decide to finish this collaboration.

AT: The backing was missing after a year?

BB: Not only the backing. The owner simply had different ideas for shorter term business success. I was aware that establishing a solid foundation for a successful collaboration is a slow and sometimes longer process. He was a little bit impatient (laughs). So, I had to finish this collaboration, and then I was a freelancer for some time.

AT: Then you worked for the Dutch-Hungarian season in Holland, which was a very successful part of your career. And, later on, an even more important stage came when you became the director of a big state-owned museum. How did you feel? For the first time in your life, you had a real adult job!

Peter Ludwig

Peter LudwigBB: It was really challenging in every sense because the Ludwig Museum in Budapest is part of the international network of Ludwig Museums. Each museum, in Cologne, Aachen, or Vienna, just to mention the biggest ones, are autonomous institutions but have a common history. All of them were initiated by the famous German collector, Peter Ludwig. He was a chocolate factory owner, and he had a very special vision about how to use contemporary art, how to merge it with the market extension strategy, mainly in the field of chocolate and in the sugar industry.

AT: So you lived like a fish in water?

BB: Yes, and each institution has a special kind of institutional mindset about the way it relates to the local art scene, e.g. the Cologne Museum belongs to the City of Cologne. In Hungary, the Ludwig is operated by the Ministry of Culture, so it is a state-run institution. Which means that, yes, I became the director of a state-run institution.

AT: A civil servant.

Ludwig Museum, Budapest

Ludwig Museum, BudapestBB: In the international scene, it is a very acknowledged position. In 2008, the Ludwig Museum was already almost 20 years old. The previous director, Katalin Néray, did a very good job, so the museum was part of the international discourse—of the international exhibition exchange. It was one of the few, one of the only, institutions in Budapest that had international expertise and a rich international collection. But it wan’t really connected to the local art scene. My idea was to integrate it much deeper into the local scene through its international recognition. At that time, the Ludwig Museum didn’t really take on the role of promoting Hungarian artists at an international level. I decided to organize traveling exhibitions, originated by the Ludwig in Budapest in collaboration with other museums, which is the relevant format to spread, distribute, and represent the Hungarian art scene at the highest level. This was one priority; the other priority was to diversify the collection, to make it systematic in terms of collecting different generations of artists, and to collect in terms of a geopolitical perspective. We started to enrich and increase the acquisitions according to these terms. Out of all the museums in the Central-European region, we belonged to the few which started to be acknowledged by the encyclopedic museum collections, like MoMA in New York and the Tate in London, so it was the beginning of a huge process. The artistic achievements of the ’60s and ’70s in the Socialist countries were starting to be recognized globally, but there was a missing link in the narrative of contemporary art history regarding what was going on in the Central-European region during the Soviet regime. Through this process—through the interpretations, through research, through the acquisitions—part of that history started to be discovered. And we wanted to be part of this process—we wanted to be the protagonists of this process. We started collaborating with neighboring countries and intensifying the acquisition and exhibition policy in this region. We made the first huge retrospective of Mladen Stilinović, one of the most important artist from the former Yugoslavia. It was a definite direction to try and represent the whole wider region based on the collection donated by Peter Ludwig, which represented the global art scene from pop art of the ’60s and ’70s to the art of the Western European countries from the ’80s. In this sense, the Ludwig Museum in Budapest has a unique position because there is no similar type of collection in the former Soviet countries, and there is also no similar collection in Western Europe.

AT: And the exchange office you established while you were there?

BB: It was before. I initiated the Agency of Contemporary Art Exchange (ACAX) in 2006 as an independent agency specializing in collaborations between the local and the international art scenes. It grew out of my previous experiences. In Hungary, there were no dedicated institutions which really supported and encouraged communication between the local and international art scene at the highest level. For example, the Ludwig Museum had a rich international collection in the ’90s and 2000s but it had no specific mission to support the participation of Hungarian artists in different biennales. As a result, artists who ended up being supported were always just by chance, and which curator of which biennale was invited to Hungary was also very arbitrary. While in the Western European countries, there is a very solid structure: there are state-run offices dealing only with these issues. They have highly professional people working on increasing networking possibilities for their local art scenes.

AT: And they have the budget.

BB: They have the budget and the capacity to invite foreign experts. They can also provide relevant support and help the realization of participation. In the ’90s, biennales became the most important events in the contemporary art scene, and they started to base their financial model on national support - invited artists who were supported by their national cultural institutions. In Hungary, there was no system for this. Only the Venice Biennale had some sort of systematic, regular support in Hungary, but even that didn’t come about until the year 2000.

AT: When you became a museum director, did you lose all your supporters, private funders, and contacts all over the world?

BB: No, I tried to make the collaborations between the private collectors and the public-run institution transparent. It certainly needs a clear consensus about the modus vivendi to work together.

AT: Not under the table but above the table.

BB: Above the table because each partner had a different mission, function, and motivation. And the interests are also different. When you use public funding in a state-run institution, it is very important that the regulations and the rules of the game be transparent, such as showing private loans in the exhibition spaces together with pieces from the permanent collection. It is always a sensitive issue. This is also an issue in German museums and even at MoMA. There is usually a public discussion about it. In Hungary there was no real consensus and no discourse around how to deal with a collector. For me, it was very important to set the rules and to be accepted by both parts. Each year I published the budget of the acquisitions: how many artworks were purchased and how much of the budget we spent on these works. In those years, this was unique for a state-run institution because many institutions didn’t care about transparency, and they probably had no real budget to speak of. Nobody had any idea about the new acquisitions of the National Gallery’s collection, for example. Now there is some kind of progress that I initiated; I suppose this is very important for the mental and moral health of the whole scene.

AT: If I have to single out one achievement in the Hungarian art scene, I must highlight the Leopold Bloom Award. It is so brilliantly conceived, and it has worked so impeccably during the last eight years. Am I right in saying that it was your idea, that you persuaded the founder, who is a businessman, to establish the award?

BB: Not exactly (laughs). I would be happy to take credit, but Mr. John Ward himself came up with the idea. However, he was aware that he didn’t really understand the fine tuning of the art world in Hungary.

AT: So he approached you?

BB: He had an idea with a clear intention: he wanted to establish an award. And he was wise enough not to start by himself. He approached different people in the arts scene: gallerists, curators, and so on. It was suggested to him to consult with ACAX. At that time, this small agency (actually it was two people) was already incorporated within the institutional framework of the Ludwig Museum. We started to discuss his idea and his preferences. After awhile, I proposed that he establish the award in addition to a very targeted subsidy, so it wouldn’t be just an award, it would also serve as relevant support for those artists who already started their career in the international scene.

AT: It focuses on early or mid-career artists?

BB: Artists who are already in the position that they have an invitation. They have opportunities, but they still need a certain kind of impulse.

AT: And the jury is only foreign curators. Three foreign curators.

BB: Yes. The idea was that artists could apply who already have a documented invitation to make an exhibition. The award could help them make the show and boost their career through the realization of an exhibition with an institution.

AT: The name is brilliant. Was it your idea?

BB: It was a common idea, if I remember correctly. Mr. Ward is an Irish guy. Between Irish and Hungarian culture…

AT: Leopold Bloom is the only link, from the Ulysses of James Joyce. Unfortunately your contract was not renewed as the director of the Ludwig, and you started your career from scratch all over again. But you have maintained ACAX.

BB: Yes, it was probably my most disliked action by the current government. In 2006, when we initiated the exchange agency, we received support from the Ministry of Culture, but the whole structure and the basic idea was mine. ACAX was supported for years by the Ministry through the budget of the Ludwig Museum. When my term expired and I was not able to continue in my post as director, I was aware that the function and the mission of ACAX could not be achieved if it stayed within the framework of the museum. I created ACAX, it was my brainchild, so I registered it as a trademark. That means they then needed my license to use it. But I wanted to continue to run it myself, so I proposed to secede it from the museum. This was not really well-received.

AT: They doubled your budget? (laughs)

BB: I immediately lost all public funding, which was a straightforward and definite statement about the current cultural policy. Since then, ACAX is an existing brand, but it is low-profile because I run it on a voluntary basis without any funding. We apply for different international funds, like EU grants, and we are lucky enough that we are supported from New York to keep at least one of the most important programs, the New York residency program, running. Residency was one of the main points of focus of ACAX ; until 2011, it was supported by public funding from Hungary. Then that funding was completely cut. We have had to stop the other residency programs in London and Berlin. Thanks to TMU we can continue the New York residency with Residency Unlimited in Brooklyn.

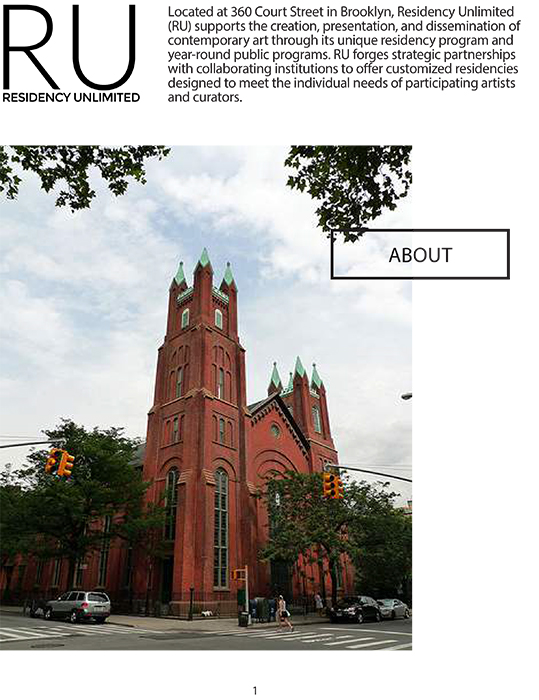

Residency Unlimited

Residency Unlimited

Right now, this is the only residency for Hungarian artists that allows them to spend a longer term at a relevant art center. It is one of the most important programs for the whole Hungarian art scene because there are no other opportunities to get fresh air and fresh ideas.

We recently initiated a collaboration with the Leopold Bloom Award, and as a result, the residency program will now be part of a new initiative of the Leopold Bloom Award, which will be focused on the younger generation. The Leopold Bloom Award is a completely private initiative financed by the founder’s own contribution, comes with a cash prize, and is awarded every two years. This new award focusing on the younger generation will happen on the off years of the original Leopold Bloom Award. We are going to run ACAX’s residency in tandem with this new award—both are granted with the residency in New York, supported by TMU. Many of the artists who were supported by TMU at Residency Unlimited really boosted their career. For example, Peter Puklus, who spent three months there in 2016, made the shortlist of the Aperture Magazine, a book project in Paris Photo, and he recently received the Grand Prix Image Vevey, which comes with incredibly generous support. The prize includes an exhibition opportunity in Vevey, a beautiful Swiss town, and 40,000 Swiss francs to create a show. It has a high reputation because the jury consists of influential individuals from the art scene, such as Christian Marclay, who is a fantastic artist, and the senior curator of the photo department of the Tate. It is really a top award. We’re so proud of Peter; I am happy to work with him at Glassyard as well.

AT: I wish you all the best with your new Glassyard Gallery, Barnabás. Thanks very much for your time.

BB: Thank you, András!

------------------Barnabás Bencsik is a curator living and working in Budapest. He earned his degree in literature, history, and history of art from ELTE University in Budapest. After university, he became involved in the changing period of the Hungarian post-Communist art scene. From 1990 to 1999, he ran Studio Gallery, the exhibition venue of the Studio of Young Artists’ Association. Parallel to this, he served as the visual arts program-coordinator at Soros Center for Contemporary Arts-Budapest. From 1999 until 2001, he ran the TRAFÓ Gallery and was chief curator in Műcsarnok|Kunsthalle, where he contributed to the exhibition of the Hungarian Pavilion at the 49th Venice Biennale. In 2001, he became the artistic director of MEO-Contemporary Art Collection. In 2002, he began working as an independent curator. He created ACAX|Agency for Contemporary Art Exchange (acax.hu) in 2006, which supports and develops various types of cooperation between the Budapest and international art scenes. He served as the director of the Ludwig Museum from 2008 until 2013. Together with Tünde Csörgö, entrepreneur and fan of contemporary art, Barnabás recently opened Glassyard Gallery, which represents and shows Hungarian and international artists and fosters collaborations between for-profit galleries and independent curators.

András Török is a Hungarian policymaker, author, nonprofit businessman, and cultural philanthropy specialist. A former dissident, teacher, translator, and editor of underground and over-ground publications, András served as Deputy Minister for Culture and as President of the National Cultural Fund from 1994 until 1998. He worked as the founding director of the Hungarian House of Photography from 1998 until 2003. András travelled extensively in the United States as a German Marshall Fellow in 1990, a USIA grantee in 1997, and a TMU grantee in 2000, 2012, 2015, and 2017. He is the author of eight non-fiction books, his most well-known being Budapest: A Critical Guide, now in its 8th edition. In 2003, in collaboration with István Arnold, András founded Summa Artium, a nonprofit business consultancy with the aim of boosting corporate and private sponsorship and support for the arts in Hungary. Summa Artium also promotes partnerships between the arts and business sectors.